![]()

Reuters, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2001

George W. Bush at an economic forum in January 2001 with Nancy Lazar of International Strategy and Investments and Enron's Kenneth Lay

Mark Wilson, Getty Images

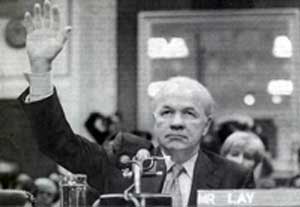

Kenneth Lay is sworn in before the Senate Commerce Committee in 2002 in Washington during a congressional investigation into Enron's collapse. He refused to testify before the panel, which some saw as a blow to his credibility.

Los Angeles Times, July 6, 2006

KEN LAY DESERVED A STATE FUNERAL

By Robert C. Keating, Editor

Enron founder Kenneth L. Lay died of a massive heart attack at a rented Aspen vacation home on July 5, 2006. He was 64.

Lay's death came only six weeks after he and former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling were found guilty of conspiracy and fraud. He was due to be sentenced in October.

Lay's memorial service on July 13 was held in Houston and skipped by all of Lay's political cronies...except the first President Bush and wife Barbara. Considering how many Washington politicians including Bush had benefited from his attentions, one might have expected a state funeral for Lay --his body resting in the Capitol Rotunda as the President and Vice President, cabinet members, Senators and Congressmen and their families filed by.

Asked how the current President Bush was taking the news of Lay's death, White House spokesman Tony Snow sniffed, "The president has described Ken Lay as an acquaintance, and many of the president's acquaintances have passed on during his time in office."

Even for a guy named Snow, that's cold.

In his dismissive remarks about the president's longtime benefactor, Tony Snow left out a few facts, well remembered by Californians who faced an unprecedented energy crisis just as Bush was taking office. (It was soon proved that Enron had been among the companies helping to engineer the crisis with trading schemes that drove up prices and pinched supplies.) As Bush took office in January, 2001, he flatly refused to intervene as California's electricity costs skyrocketed and utility companies declared bankruptcy. Bush suggested that (1) Californians cut their energy consumption, which was actually unchanged from the year before, and (2) purchase electricity from neighboring Mexico.

Something smelled fishy in this new administration right off the bat. Soon it came to light that there was a series of "task force" meetings between Bush and Cheney and Lay and other energy executives before the administration's new energy policy was unveiled. In a fight the Bush administration took all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, it has refused to divulge details of those meetings to the Inspector General of the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Fears of White House corruption were made more real just 22 days after Bush was sworn into office, when the Los Angeles Times reported that Lay and Bush had a friendship going back years, and that "Bush repeatedly flew on Enron jets during the campaign." With Enron's collapse still months away, the Bush administration hadn't yet started to cover its tracks. The story shows a reality at sharp variance with Tony Snow's official version:

© 2006 Most Corrupt.com

Los Angeles Times

February 11, 2001

BUSH'S TIES TO ENRON CHIEF ATTRACT GROWING SCRUTINY

Presidency: Their close friendship over the years has new significance because of the Texas energy firm's role in California's power market.

By Edwin Chen and Judy Pasternak

WASHINGTON--To hear Kenneth L. Lay tell it, you'd think he's just another guy who occasionally hands out free advice to his longtime friend, who now happens to be president.

But the voluminous correspondence between the chairman of Houston-based Enron Corp, a giant energy marketing firm, and President Bush suggests otherwise. The "Dear Ken" and "Dear George" letters reveal long-standing personal and professional relationships that are intimately intertwined....

Over the years, Lay has sent Bush reading material, urged him to attend meetings around the world, recommended people for jobs in Austin, Texas, and thanked him for lobbying a fellow governor on Enron's behalf. in one postscript, Lay wrote, "George, Linda and I are incredibly proud of you and Laura."

For his part, Bush updated Lay on his knee surgery while ruing the fact that he had to miss a 10k race in Austin. When Lay turned 55, Bush sent him a teasing note that said in part: "Wow! that is really old."

Their mutual affinity is emblematic of the larger ties between Bush and the energy industry. While there are no signs of impropriety or wrongdoing, those connections are coming under growing scrutiny now that Bush has settled into the White HOuse.

Of particular concern to some Californians, Bush repeatedly has refused to intervene more aggressively in the state's electricity crisis--even as Enron and its subsidiaries have profited handsomely from soaring energy prices.

Moreover, Bush has assembled an administration with unprecedented connections to the energy industry. A former oilman himself, Bush has chosen a vice president, a commerce secretary and a national security advisor with energy industry ties.

"To separate him from that industry is hard to do. There are so many connections," said Craig McDonald, head of the nonprofit Texans for Public Justice, a political watchdog group. "There's always been a question of whether the policies he's pursuing are his or Ken lay's. Actually, there is no difference."

Mark Cooper, research director for the Consume dr Federation of America, expressed his concerns as a question: "Now that George Bush is president and faces a broader range of interests, as you must as president, will he listen to other points of view and come up with a compromise answer? We shall see."

Dan Bartlett, deputy counselor to the president, said that Bush's connection to the energy industry is an asset. "The American people will appreciate President Bush's understanding and insight on such a complex issue," he said. "And he's making it a priority for this country to have a national energy policy."

There is no corner of the energy industry that is better connected to Bush than Enron, which has made billions of dollars by matching buyers and sellers of natural gas and electric power. It is, as Fortune magazine put it last year, "far and away the most vigorous agent of change in its industry, fundamentally altering how billions of dollars' worth of power...is bought, moved and sold, everywhere in the nation."

Amid the escalating energy crisis, Enron's core business reported income of $777 million in the fourth quarter of 2000--nearly triple that of a year earlier, according to Business Week.

Although many energy executives and companies have given generously to Bush's political endeavors, Enron and Lay stand out.

Now 58, Lay was a strong backer of the current president's father, former President Bush. After the elder Bush's defeat by Bill Clinton in 1992, Enron hired his secretary of State, James A. Baker III, and his Commerce secretary, Robert A. Mosbacher, as consultants.

In Austin, Lay became a patron of George W. Bush and donated more than $500,000 to his campaigns, according to the Center for Public Integrity, a Washington-based watchdog organization.

Lay was also a member of the prestigious governor's business council, which advised Bush on such matters as deregulating electric utilities, easing the tax burden on businesses and enacting tort reform.

"Mr. Lay offered fantastic advise for us on how we open markets," recalled Jimmy Glotfeldy, a one-time policy aide to then-Gov. Bush.

When Bush first considered a run for the White House, Lay became one of 200 or so "pioneers," each committed to raise at least $100,000.

During the campaign, Bush repeatedly flew on Enron jets. Enron also contributed $250,000 for the Republican National Convention. During the Florida recount, Lay personally donated the legal limit of $5,000 to the effort and $100,000 to Bush's inaugural committee.

"I am a strong supporter of the president, as I was with his father. I've known him and his family for a long time," Lay said during a recent meeting with The Times' editorial board.

But hare added: "Probably my influence over the president or my advice to the president is grossly exaggerated."

Just five days later, Lay was among a small group of business executives having lunch with the president at the White House. At the time, Bush was playing down the need for a federal role in California's energy problems.

More recently, lay discussed California's energy crisis with Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham and Treasury Secretary Paul H. O'Neill. Lay said he warned both Cabinet officers that the crisis would have "serious [national] implications" and that "the federal government needs to...at least have some contingency plans."

Bush soon showed far more interest in the crisis. "We have an issue in America right now called energy," he said during an appearance Tuesday to tout his tax cut plan.

Enron's Oval Office connection is not the only one it enjoy7s in the Bush administration.

Until they accepted job offers from the new president, Lawrence B. Lindsey, now the White House economic advisor, and Robert B. Zoellick, the U.S. trade representative, served on Enron's advisory board.

But nothing can top the bond between Lay and Bush, as illustrated by their letters and notes, obtained by The Times under the Texas Open Records Act.

On Oct. 17, 1997, Lay thanked then-Gov. Bush for calling Pennsylvania Gov. Thomas J. Ridge, a fellow Republican, to vouch for Enron, which was competing to sell electricity in that state.

"I am certain that will have a positive impact on the way he and others in Pennsylvania view our proposal," Lay wrote.

He was not disappointed. A short time later, Enron gained a foothold in the Pennsylvania electricity market.

But not all the back-and-forth involved business.

Shortly before Thanksgiving in 1997, Lay offered his condolences that Bush, an avid runner, would be undergoing arthroscopic knee surgery.

"But I also want you to know that at least one jogger [me] got past 50 without surgery," Lay wrote.

"All went well," Bush replied. "And I am feeling great. I was able to get back to work almost immediately. My only regret is that I will be benched from jogging for about a month."

© 2001 Los Angeles Times

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Insiders in the Bush administration are always looking for what they call "page turners"...news events that will help take the public's mind off whatever grim event the White House is trying to recover from. America needs page turners of a different sort...looking back to what actually happened before the spin cycle, to see how we got into the mess we're in.

The Los Angeles Times editorial that follows appeared less than a year after the story above, as Enron went up in flames and company employees and others saw their pension plans go worthless. By then Washington players were removing Ken Lay from their speed dials and deleting his emails.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ENRON'S FAR-REACHING WEB

January 19, 2002, Los Angeles Times Editorial -- The Enron debacle is long past being a story about the fall of a corporation. Enron's tentacles stretch far and wide, to accounting firms, the Securities and Exchange Commission, Congress, the White House, the Justice Department, even journalists. The question is becoming not who was tainted by Enron but who wasn't. It is an object lesson in why the SEC, the campaign finance system, the government culture itself need reform. With so few left untainted, who is trustworthy to clean up the mess?

Consider the Bush administration, which has 35 officials who have held Enron stock. Top political advisor Karl Rove's stock was worth six figures. President Bush, despite his lame attempt to associate Enron head Kenneth L.Lay with former Texas Gov. Ann Richards, has long enjoyed a close relationship with him. Presidential economic advisor Lawrence B. Lindsey received $50,000 as an Enron "advisor." Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft recused himself from the criminal investigation because he had received a hefty Enron contribution to his 2000 senatorial campaign.

Given these and many more links, it is ever more disturbing that Vice President Cheney obstinately refuses to divulge detailed information about his energy task force's numerous meetings with Enron's executives.

Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-Los Angeles) has released another study showing that numerous policies in the White House energy plan were virtually identical to those espoused by Enron; no fewer than 17 policies, including deregulation initiatives and support for trading in energy derivatives, would have benefited the corporation.

By no means did Enron confine its efforts to the White House. On the contrary, Capital Hill lawmakers eagerly partook of Enron's booty. Power couple Seen. Phil Gramm (R- Texas) and Wendy Gramm constitute a study in conflicts of interest in themselves. Wendy Gramm is a member of Enron's board; her husband was pivotal in permitting Enron to receive an energy trading exemption.

As The Times' Mark Fineman revealed Friday, none of the key congressional committees investigating Enron or its former auditor, the Andersen company, would be able to summon a majority if they excluded members who had received campaign contributions from either company. Sen. Joseph I. Lieberman (D-Conn.), one of the chief investigators, accepted thousands of dollars from both. Rep. W. J. "Billy" Tauzin (R-La.), who is aggressively investigating, raked in contributions from the two companies. Lieberman and Tauzin are running away from Enron as fast as they can, but the contributions will always distort public perception of their actions.

Few have been more fervent in denouncing the culture of greed that led to debacles such as Enron than New York Times economics columnist Paul Krugman. Yet it now turns out that Krugman himself was paid $50,000 as an Enron consultant in 1999, even though his position had "no function" that he was aware of.

After Sept. 11, polls showed that the American public had greater confidence in government and other institutions. The Enron scandal threatens to swiftly reverse that trend. There could be no better argument for political and regulatory reforms.

© 2002 Los Angeles Times